Mixing Documentation to Code and REST APIs

1. Introduction

There is an ongoing debate among people focusing on software documentation about the best way to document an API. One approach suggests that you create the document first, and then the developers develop the code to implement the definitions. The other approach proposes using the source code as documentation by extending it with special comments used to generate human-readable documentation.

In this article, I will discuss the pros and cons of both approaches, and then I will suggest a middle ground, allowing you to move as many documentation fragments into the code as you prefer.

2. Should APIs be documented with code?

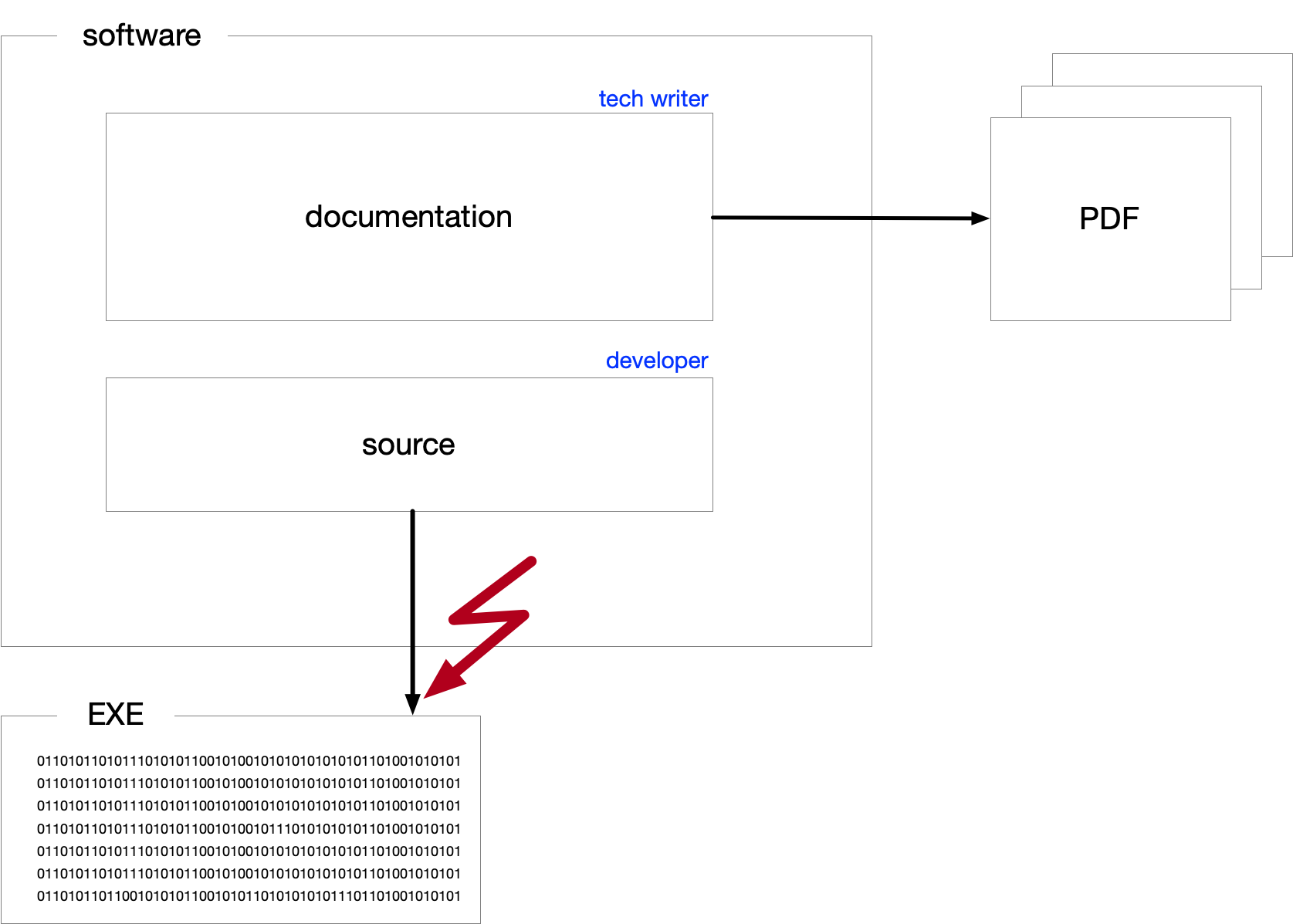

When we talk about embedding documentation in the code, we refer to text used to generate the product. A software product is a set of text files that undergo different transformations, resulting in:

-

an executable environment, and

-

human-consumable documentation.

The first one includes the machine code, the configuration of the environment, and generally everything technically needed to have functioning software. The second is necessary to empower users to utilize the software.

2.1. Separate Documentation and Source

Some of the text files in the software product are used to generate the executable environment, while others are part of the documentation. Historically, these two sets have been separate and maintained by different people: software developers and documentarians. The text files used to create the executable are called program source code, or source for short, while the others are called documentation. These two types of files have different traits.

-

Source code is formal, usually written in a programming language, consumed by programs, and it must be precise.

-

Documentation is written for human readers, using natural language, and it must focus on clarity, simplicity, and usability more than precision.

One could say that documentation is the code executed by human "processors" to operate and use the code executed by machine processors.

Humans can handle errors in their input and interpret the documentation intelligently. If there is a typo, slight inconsistency, or deviation from the actual product, the documentation may still be usable. Humans can interpret, understand, and use imperfect documentation. This does not mean that documentation with errors is acceptable. It simply means that, while it may be usable with some errors, you should still strive to avoid errors, of course.

2.2. Mixing Documentation and Source

Modern applications mix documentation with the source to some extent. There are clear advantages to doing this.

The source contains information that the documentation can rely on. Why manually write something into a separate document, risking inconsistency when it is already in the source? Automatically extracting the information from the source code and transforming it into a human-readable document should be cheaper than manually following changes in the source and mirroring them in the documentation.

Part of the documentation is strongly tied to the code and is maintained by the developers. It is logical to tie the documentation to the code by placing them in the same text file. It is less likely that you will skip updating the related document for a changing code when the document text is in the same place, in the same file.

There are also drawbacks to mixing documentation with the source code. Documentarians are not necessarily developers. It may be a barrier to edit a text within a source file, as this is part of the code. It may require specialized skills and privileges to modify the source code, even if only the documentation part is being changed.

It also introduces a new possibility for documentation processing: failure.

Conventional documentation is a simple conversion process that rarely fails. You export the document to PDF or another output format.

When using a textual document, the conversion may signal an error if there are errors in the markup. Luckily, documentarians have become accustomed to markup languages and to the possibility of such errors. Using markup instead of WYSIWYG editors is becoming a no-brainer.

When the document is partially in the source code, the situation becomes more complex. The conversion may fail due to inconsistencies between the documentation and the code. The documentarian must understand the code to fix the documentation.

While this can be a barrier to overcome, you can also view it as an advantage. It can provide a semantic check on the documentation, which was previously only possible through manual reviews.

2.3. Mixed Parts

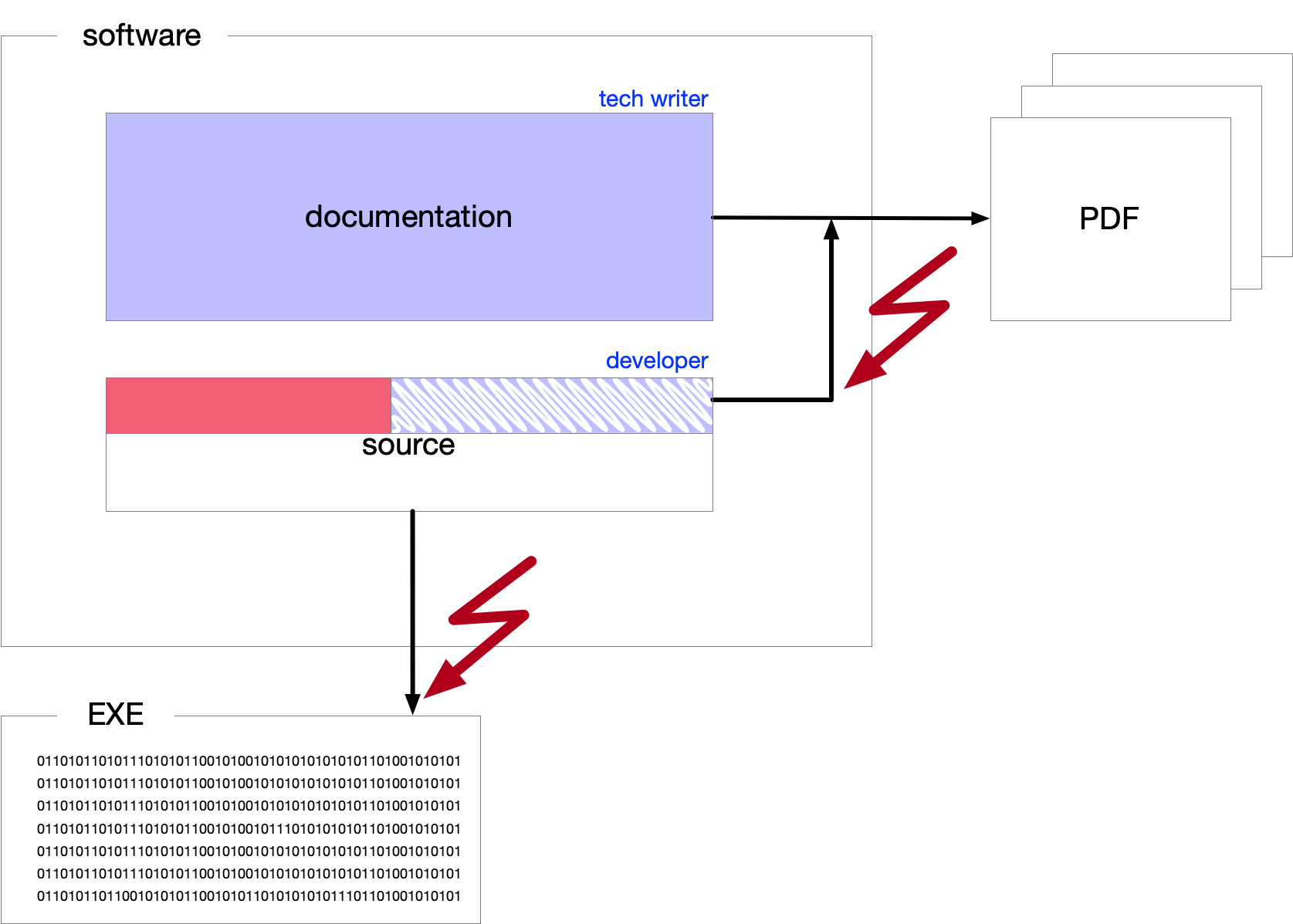

When we talk about source code as part of the documentation, we can separate three different parts of the text.

-

One part is pure documentation included in the source code, denoted in blue in the diagram "Mixed Documentation and Source." If there is any change in this text, typically a comment, the code will still produce the same executable.

-

The second part is actual source code used by the documentation. It is denoted in red. This part is the actual code that gets into the executable but also affects the documentation.

-

The third part is represented by the blue striped area, representing the source affecting the documentation but not the executable. This part of the documentation is meta-information that helps the documentation generator create the human-readable documentation from the source code. It is usually a comment from the program’s point of view.

2.4. Simple Examples of Mixing

The most well-known examples of mixing documentation and source code are JavaDoc and Doxygen. Less known, but the earliest such application I found was Perl POD documentation from 1989. Newer technologies include GoDoc, RDoc, PHPDoc, XML Comments in C#, and many others, including the already mentioned JavaDoc and Doxygen.

Another example is Swagger/OpenAPI. The Swagger specification usually uses YAML to describe the API. This description contains technical parameters (source) and human-readable descriptions (documentation). The documentation is useful for maintainers when they write the code implementing the API. At the same time, the generated documentation is useful for the API’s users.

However, API users need additional information. The application API is only an interface to an application that may itself be complex. The documentation must explain the application’s purpose, usage, different use cases, and so on. This information is not part of the Swagger specification. Technically, you can include it in the Swagger specification, but it is not the best place for it.

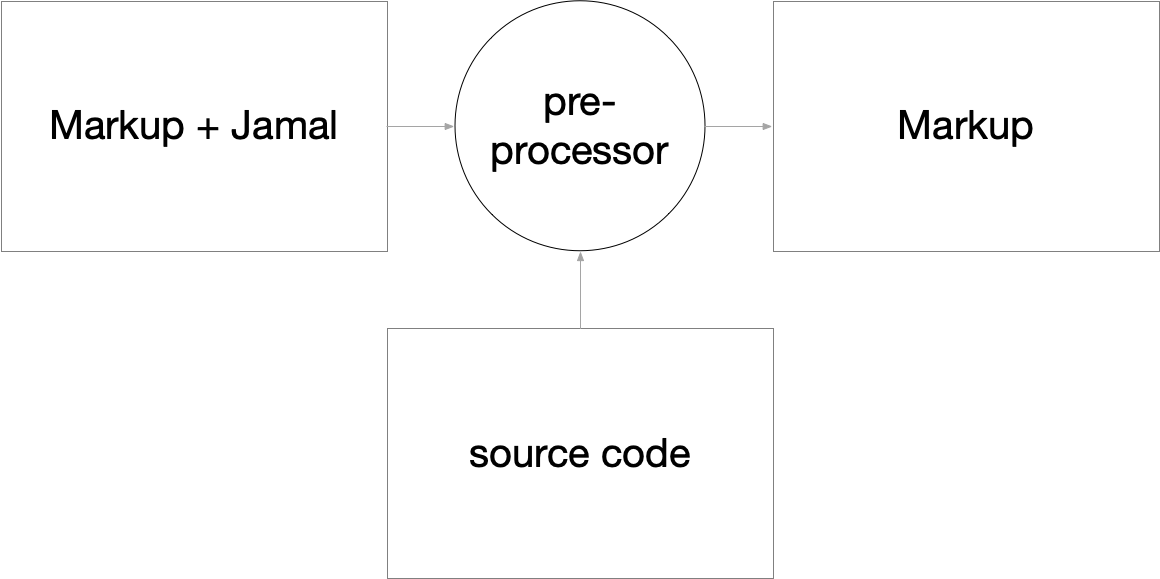

2.5. Modern Way of Mixing

The modern way of mixing documentation and source code is to use a tool that can combine documentation markup with information from the code. There are many different tools that can do this. Most of these tools support textual, markup-formatted documents, extending the basic markup language. The actual execution can occur as a preprocessor or by modifying the markup processor.

Using the extra meta-markup language has some drawbacks.

-

It is an extra language to learn.

-

It is simpler to copy something like a configuration parameter name into the documentation than to add meta-information to the code and reference it from the documentation.

-

Receiving warnings or errors about inconsistencies between the documentation and the code can be annoying.

At the same time, these can also be advantages, except perhaps the first one.

If you reference a configuration name instead of copying it, the documentation will remain consistent when the developer changes it. Warnings about inconsistencies can be beneficial. While receiving a warning may be annoying, it is better than having unnoticed inconsistencies in the documentation.

In the following section, I will show a few examples of how to handle these situations using the Jamal meta-markup document processor. It is only fair to mention that I am the author of Jamal. There are other tools you can use, and you should choose the one that best fits your needs. In my non-humble opinion, Jamal is the best tool for documentation purposes.

2.6. Examples Using Jamal

Jamal is a general-purpose meta-markup processor. It is a Java application, but this should be the last thing you worry about. It works on Linux, macOS, and Windows. The installation is simple. You download the installation kit for your architecture, start it, click a few times on "continue," and you’re all set.

The homepage for Jamal is https://github.com/verhas/jamal

The conversion can be done from the command line, but it is also integrated into the IntelliJ Asciidoctor plugin and AsciidocFX editor. In these cases, you can edit Asciidoc and Markdown documents WYSIWYG, including the Jamal meta-markup commands, and the conversion happens automatically.

|

Note

|

When you edit a Markdown document, the meta-markup preprocessor will convert it to Asciidoc in the memory of the editor, and the editor will think you are editing an Asciidoc document, displaying it formatted. This is a little workaround needed because the Markdown plugin for IntelliJ does not support preprocessor integration. Similarly, you can edit XML and other formats with Jamal meta-markup, and they will be displayed through the Asciidoctor plugin. There are video tutorials installing and configuring Jamal: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6uBseiZlQg |

2.6.1. Consistency Check

The simplest example is a consistency check.

Some segments of the documentation are closely related to specific parts of the source code. In that case, it would be helpful to receive a warning if the part of the source code has changed since the documentation was updated.

Let’s look at an example!

|

Note

|

The URLs in this article point to a specific commit in the repositories so that the examples remain stable. |

The source code for the documentation of the Jamal IO package at line 290:

contains the following line:

{%@snip:check id=java_echo_version hashCode=5dd285e7%}The Java code TestExec.java at line 24:

contains the following lines:

// tag::java_echo_version[]

System.setProperty("exec", "java");

// end::java_echo_version[]The documentation includes these lines verbatim as a demonstration.

It also explains what the code does.

What happens when the code changes and the explanation becomes inconsistent with the new code?

There is no way (currently) to update the document without manual human work, but at least we can detect the possible inconsistency.

The snip:check meta-markup calculates the actual hash code of the snippet and compares it to the hash code stored in the meta-markup.

If it is different, the processing of the document will issue a warning, giving the documentarian a chance to update the document, make it consistent with the actual version of the code, and then update the hash code.

(The error message contains the correct hash code and even a sed command to update the document with a single command.)

The meta-markup can check against the hash code or the number of lines in a snippet or a whole file, increasing the coupling between the documentation and the code, resulting in better consistency.

2.6.2. Include Code in Documentation

The next example is when the documentation includes part of the actual code, but not as a code sample.

The Jamal meta-markup processor has many modules, including one that implements a simple BASIC-like programming language.

This programming language has keywords.

The keywords are defined in a Java source file called Lexer.java at line 16:

final static private Set<String> RESERVED = Set.of(

//snipline KEYWORDS

"if", "else", "elseif", "then", "endif", "while", "wend", "for", "next", "do", "until", "and", "or", "not", "to", "step", "end"

);The documentation:

includes the list of keywords with the line:

The keywords are {%#replace (regex) /{%@snip KEYWORDS%}/"/`/%}.The Java comment snipline signals to the processor that the next line is a snippet that will or may be included in the documentation with the name KEYWORDS.

The documentation includes the snippet with the snip meta-markup and also transforms it, replacing the double quotes with backticks.

This will essentially list the keywords found in the code without copying them into the documentation manually.

The "copy" will be done by the meta-markup processing.

If the list of keywords in the code ever changes, the documentation will be updated automatically.

2.6.3. Fetch Version Number

Another example is fetching version numbers from the pom.xml file.

Documentations often refer to the "latest version" in sample code or other places when talking about the current version.

Why ask the reader to look at the release history or the pom.xml file while reading the documentation?

Reading the documentation should be frictionless, without requiring the reader to search elsewhere.

Getting version information from another source is not the reader’s task.

It can be done by the documentation generator.

The same README.adoc.jam file we used in the previous example contains the following lines:

{%@snip:xml pom=pom.xml%}\

{%#define VERSION={%pom /project/version/text()%}%}\

[source,xml]

----

<dependency>

<groupId>com.javax0.jamal</groupId>

<artifactId>{%pom /project/artifactId/text()%}</artifactId>

<version>{%VERSION%}</version>

</dependency>

----This fetches the version number from the pom.xml file and uses it in the documentation.

2.6.4. Documentation in the Code

Sometimes it makes sense to include part of the documentation inside the source code.

An example of this is the documentation of the parameter options for the for meta-markup command.

The source code that implements the parameter option handling is:

and it contains the following code:

public ForState(Scanner.ScannerObject scanner, Processor processor) {

this.processor = processor;

// snippet parops_for

separator = scanner.str("$forsep", "separator", "sep").defaultValue(",");

// can define the separator if it is different from the default, which is `,` comma.

// The value is used as a regular expression, providing very versatile possibilities.

subSeparator = scanner.str("$forsubsep", "subseparator", "subsep").defaultValue("\\|");

// can define the subseparator if it is different from the default, which is `|` pipe.

// It is used when there are multiple variables in the loop.

// Similarly to the separator, the value is used as a regular expression.

trim = scanner.bool("trimForValues", "trim");

// is a boolean parameter.

// If present and `true`, the values are trimmed, removing spaces from the beginning and end.

skipEmpty = scanner.bool("skipForEmpty", "skipEmpty");

// is a boolean parameter.

// If present and `true`, empty values are skipped.

lenient = scanner.bool("lenient");

// is a boolean parameter.

// If present and `true`, the number of values in the list is not checked against the number of variables.

evalValueList = scanner.bool("evaluateValueList", "evalist");

// is a boolean parameter.

// If present and `true`, the value list is evaluated as a macro before splitting it into values.

join = scanner.str("$forjoin", "join").defaultValue("");

// is used to join the values together.

// The default is the empty string.

// end snippet

}This is the code defining the parameter options, and each line declaring a parameter option programmatically is followed by one or more comment lines describing the option. What the processing will need is to include this information, with some text transformation, into the documentation.

The Asciidoc document incorporating the documentation from these lines is:

with the following code:

The options are

{%@snip:collect from=../../jamal-core/src/main/%}

{%#replaceLines replace="/.*?scanner\\.\\w+\\((.*?)\\).*/* $1/" replace="/\"/`/" replace=|^\s*//|

{%@snip parops_for%}

%}The snip:collect meta-tag instructs the processor to collect snippets from the source directory.

The following lines reference the snippet named parops_for and transform it with three regular expression search-and-replace actions.

First, it looks for the string scanner and transforms the program line into a list bullet with the strings, which are the alternative names of the options.

Next, it replaces double quotes with backticks.

Finally, the last step removes the // from the start of the comment lines.

This results in an itemized list of the options in the documentation. If any new option is inserted or one is deleted, the list will automatically update. The developer is less likely to forget to add the documentation because it is right there, following the declaration of the parameter option.

2.6.5. Mixing Swagger YAML with Documentation

The last example is mixing the documentation included in the Swagger YAML file with the main documentation. OpenAPI YAML files define the API of a REST service, and they can contain the documentation of the API. However, the documentation of the API is different from the documentation of the application. The latter can, and usually should, include the first one.

The example is the OpenAPI YAML file of the AxsessGard application:

There is nothing special about this file. It is structured, and since Jamal supports reading YAML structures, there is no need to add snippet markers to the file.

The Asciidoc documentation using the information from the YAML file is:

and it contains the following lines:

{%#yaml:

define api={%@include [verbatim] src/main/resources/openapi.yaml%}%}

{%@yaml:format prettyFlow flowStyle=BLOCK%}

{%@yaml:set paths=/api.paths%}

{%!@for $path from paths=

{%!@for $METHOD in (get,post,put)=

{%#if|{%@yaml:get (from=api) (paths['$path'].$METHOD != null)%}|

=== {%@case:upper $METHOD%} `$path`

{%@yaml:get (from=api) (paths['$path'].$METHOD.description)%}

%}

%}%}This code:

-

reads the YAML file while processing the documentation,

-

loops through the list of paths in an outer loop,

-

loops through each existing method in an inner loop, and

-

creates a section for each method in each path, including the description of the method.

This last one is a fairly complex example, using very advanced features of the Jamal meta-markup processor. The result is a documentation that contains both the application documentation and the API documentation in one place. If the API documentation changes, it will automatically be included in the application documentation.

3. Conclusion and Summary

In this article, we discussed the structure of software documentation, how it is created separately in documentation files, and how it can be partly embedded in the source code. We explored how information in the source code can be used to help generate the documentation. While integrating information from the source code has its challenges, it also offers advantages. In my opinion, the disadvantages stem from:

-

Human reluctance to adopt any new technology that must be learned.

-

The increased complexity of the documentation process, which

-

is unavoidable if you want better automation supporting consistency and better, automated documentation updates,

-

partially arises from the immaturity of currently used tools.

-

However, the advantages balance these drawbacks by following the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle, which has been applied in programming for over half a century. I also demonstrated the use of a tool that is universal and supports any documentation format. It presents the opportunity to mix documentation and source code in a way that best suits documentarians.

There are tools available. There are no excuses to manually update documentation when automation could handle it.

Comments

Please leave your comments using Disqus, or just press one of the happy faces. If for any reason you do not want to leave a comment here, you can still create a Github ticket.