[JAVA MAGAZIN] Code Generation 2

In this article, I will talk about code generation, why we need code generation and how to do code generation. I will describe the general problem that makes code generation a necessity and a bit of theory (not too much). I will also discuss the different phases of software development where the source code can be generated programmatically and compare the different approaches. I will also describe the architecture and the ideas (the kind of eureka moment) of a specific tool that generates code at a specific phase.

1. Why we generate code

To generate code or not to generate code, that is the question. We can ask that with Shakespeare. Practice, just like in Hamlet, gives the answer. We do generate code. Many developers generate code. Even if we do not like that. Tool generated code gives us some bad feeling. It makes us feel that something is not professional or at least not optimal. But such is life. There are only a few things that are optimal and we still have to live with these. So is the case with automated code generation.

The main reason to automatically generate code is that we do not know better. The manual code generation can be cumbersome and error-prone and the language, the framework or simply our experience and knowledge does not allow a simpler solution. And the main take-away from this article is already here at the very start. Before deciding to use code generation we have to identify the reason, why we need it.

You should not generate code unless you really have to.

Weird statement, especially when I "promote" a FOSS tool that is exactly targeting Java code generation. I know, and still, the statement is that you have to write all the code you can manually. Unfortunately, or for the sake of the tool, there are enough occasions when manual code generation is not an option, or at least automated code generation seems to be a better option.

2. Why to generate at all

When the best option is to generate source code then there is something wrong or at least suboptimal in the system.

-

the developer creating the code is sub-par,

-

the programming language is sub-par, or

-

the environment, some framework is sub-par.

Do not feel offended. When I talk about the "sub-par developer" I do not mean You. You are well above the average developer last but not least because you are open and interested in new things proven by the fact that you are reading this article. However, when you write a code you should also consider the average developer Joe or Jane, who will maintain your program sometime in the future. And, there is a very specific feature of the average developers: they are not good. They are not bad either, but they, as the name suggests, are average.

2.1. Legend of the sub-par developer

It may happen to you what has happened to me a few years back. It went like the following.

Solving a problem I created a mini-framework. Not really a framework, like Spring or Hibernate because a single developer cannot develop anything like that. (It does not stop though some of them trying even in a professional environment, which is contradictory as it is not professional.) You need a team. What I created was a single class that was doing some reflection "magic" converting objects to maps and back. Before that, we had toMap() and fromMap() methods in all classes that needed this functionality. They were created and maintained manually.

Luckily I was not alone. I had a team. They told me to scrap the code I wrote, and keep creating the toMap() and fromMap() manually. The reason is that the code has to be maintained by the developers who come after us. And we do not know them as they are not even selected. They may still be studying at the university. They may not even be born. We know one thing: they will be average developers and the code I created needs a tad more than average skills. However, maintaining the handcrafted toMap() and fromMap() methods does not require more than the average skill, even if the maintenance is error-prone. But that is only a cost issue that needs a bit more investment into QA and is significantly less than hiring ace senior developers.

You can imagine my ambivalent feelings as my brilliant (feel the irony) code was refused with a cushion that praised my ego. I have to say, they were right.

2.2. Sub-par framework

Well, many frameworks are in this sense sub-par. Maybe the expression "sub-par" is not really the best. For example, you generate Java code from a WSDL file. Why does the framework generate source code instead of Java byte-code? There is a good reason.

Generating byte code is complex and need special knowledge. It has a cost associated with it. It needs some byte-code generation library like Byte Buddy. It is more difficult to debug for the programmer using the code and is a bit JVM version dependent. In case the code is generated as Java source code, even if it is for some later version of Java and the project is using some lagging version, the chances are better, that the project can some way downgrade the generated code in case this is Java source than if it is byte code.

2.3. Sub-par language

Obviously, we are not talking about Java in this case, because Java is the best in the world and there is nothing better. Or is it? If anyone claims about just any programming language that the language is perfect, ignore that person. Every language has strengths and weaknesses. Java is no different. If you think about the fact that the language was designed more than 20 years ago and according to the development philosophy it kept backward compatibility very strict, it simply implies that there should be some areas that are better in other languages.

Think about the equals() and hashCode() methods that are defined in the class Object and can be overridden in any class. There is no much invention overriding any of those. The overridden implementations are fairly standard. In fact, they are so standard that the integrated development environments each support generating code for them. Why should we generate code for them? Why are they not part of the language in some declarative way? Those are questions that should have very good answers because it would really not be a big deal to implement things like that into the language and still they are not. There has to be a good reason, that I am not the best person to write about.

There is another example: the lambda expression. It was introduced into the language recently, only five years ago. Before that programmers had to use something else, for example, anonymous classes. Let’s put aside the fact that the performance and the byte-code implementation of an anonymous class are not the same as that of a lambda expression. The lambda expression could be introduced into the language prior to version 8 using a code generator that generated the anonymous classes from some shortened form. Some features, like lambda, multi-line strings, switch expressions were, or are not part of the language because of the language evolution. A feature which has not been proven to be really good cannot be implemented into such a language as Java. There should be experiments in other languages, the industry, the developers have to accept the feature in other languages. At that point, it can be implemented in Java and then it will stay there for decades, perhaps for centuries.

As a summary of this part: if you cannot rely on the manually generated code, you can be sure that something is sub-par. This is not a shame. This is just how our profession generally is. This is how nature goes. There is no ideal solution, we have to live with compromises.

And now we will look a bit at some theory, which explains why it is like that.

3. Redundant code

The root cause and the real reason why we have to generate code is redundancy. The sub-par developer, language or framework or anything is because of redundancy. The Wikipedia page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redundant_code defines redundant code as

In computer programming, redundant code is source code or compiled code in a computer program that is unnecessary, such as…

This is only part of the redundancy that I want to talk about. As a matter of fact, this is the last type of redundancy and in case this redundancy is answered by code generation that is the best example when NOT to generate code. In this article, I refer to redundancy more in the information theory meaning. Have a look at the Wikipedia page:

In Information theory, redundancy measures the fractional difference between the entropy H(X) of an ensemble X, and its maximum possible value log(|A_X|)

This is a very precise, but highly unusable definition for us. Luckily the page continues and says:

Informally, it is the amount of wasted “space” used to transmit certain data. Data compression is a way to reduce or eliminate unwanted redundancy.

In other words, some information encoded in some form is redundant if it can be compressed. For example, downloading and zipping the text of the classical English novel Moby Dick will shrink its size down to 40% of the original text. Doing the same with the source code of Apache Commons Lang we get 20%. It is definitely NOT because of this “code in a computer program that is unnecessary”. This is some other “necessary” redundancy. English and other languages are redundant, programming languages are redundant and this is the way it is.

4. Levels of Redundancy

Then the next question is if these are the only reasons for redundancy. The answer is that we can identify six different levels of redundancy including those already mentioned.

4.1. 0 Natural

This is the redundancy of the English language or just any other natural language. This redundancy is natural and we got used to it. The redundancy evolved with the language and it was needed to help the understanding a noisy environment. We do not want to eliminate this redundancy, because if we do we may end up reading some binary code. For most of us, this is not really appealing. This is how human and programmer brain works.

4.2. 1 Language

The programming language is also redundant. It is even more redundant than the natural language it is built on. The extra redundancy is because the number of keywords is very limited. That makes the compression ration from 60% percent up to 80% in the case of Java. Other languages, like Perl, are denser and alas they are less readable. However, this is also a redundancy that we do not want to fight. Decreasing the redundancy coming from the programming language redundancy certainly would decrease readability and thus maintainability.

4.3. 2 Structural

There is another source of redundancy that is already independent of the language. This is the code structure redundancy. For example when we have a method that has one argument then the code fragments that call this method should also use one argument. If the method changes for more arguments then all the places that call the method also have to change. This is a redundancy that comes from the program structure and this is not only something that we do not want to avoid, but it is also not possible to avoid without losing information and that way code structure.

4.4. 3 Domain induced

We talk about domain induced redundancy when the business domain can be described in a clear and concise manner but the programming language does not support such a description. A good example can be a compiler. This example is in a technical domain that most programmers are familiar with. A context-free syntax grammar can be written in a clear and nice form using BNF format. If we create the parser in Java it certainly will be longer. Since the BNF form and the Java code mean the same and the Java code is significantly longer we can be sure that the Java code is redundant from the information theory point of view. That is the reason why we have tools for this example domain, like ANTLR, Yacc and Lex and a few other tools.

Another example is the Fluent API. A fluent API can be programmed implementing several interfaces that guide the programmer through the possible sequences of chained method calls. It is a long and hard to maintain way to code a fluent API. The same time a fluent API grammar can be neatly described with a regular expression because fluent APIs are described by finite-state grammars. The regular expression listing the methods describing alternatives, sequences, optional calls, and repetitions is more readable and shorter and less redundant than the Java implementation of the same. That is the reason why we have tools like Java::Geci Fluent API generators that convert a regular expression of method calls to fluent API implementation.

This is an area where decreasing the redundancy can be desirable and may result in easier to maintain and more readable code.

4.5. 4 Language evolution

Language evolution redundancy is similar to the domain induced redundancy but it is independent of the actual programming domain. The source of this redundancy is a weakness of the programming language. For example, Java does not automatically provide getters and setters for fields. If you look at C# or Swift, they do. If we need them in Java, we have to write the code for it. It is boilerplate code and it is a weakness in the language. Also, in Java, there is no declarative way to define equals() and hashCode() methods. There may be a later version of Java that will provide something for that issue. Looking at past versions of Java it was certainly more redundant to create an anonymous class than writing a lambda expression. Java evolved and this was introduced into the language.

The major difference between domain induced redundancy and language evolution caused redundancy is that while it is impossible to address all programming domains in a general-purpose programming language, the language evolution will certainly eliminate the redundancy enforced by language shortages. While the language evolves we have code generators in the IDEs and in programs like Lombok that address these issues.

4.6. 5 Programmer induced

This kind of redundancy correlates with the classical meaning of code redundancy. This is when the programmer cannot generate good enough code and there are unnecessary and excessive code structures or even copy-paste code in the program. The typical example is the before mentioned "Legend of the sub-par developer". In this case, code generation can be a compromise but it is usually a bad choice. On a high level, from the project manager point of view, it may be okay. They care about the cost of the developers and they may decide to hire only cheaper developers. On the programmer level, on the other hand, this is not acceptable. If you have the choice to generate code or write better code you have to choose the latter. You must learn and develop yourself so that you can develop better code.

5. When to generate code?

After we have discussed the different levels or causes of code redundancy the next question is how to generate the code. In the case of language evolution, the answer is easy. There are tools, which we use. Let’s use them and they will generate the code whenever. To eliminate or lessen domain induced redundancy we created the Java::Geci framework that lets the programmers write their own code generators specific to the programming domain. The structure and the decision where to insert the code generation phase was driven by the desire to provide an easy and lovable API where it is extremely simple to create a code generator. So here we will look at the different development lifecycle phases when the code generation may happen and then we describe why Java::Geci uses the one it does.

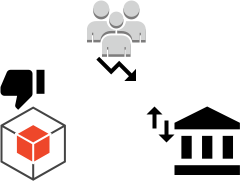

Code generation principally can happen: image::https://javax0.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/phases-1.png[]

-

(BC) before compilation

-

(DC) during compilation

-

(DT) during the test phase

-

(DCL) during class loading

-

(DRT) during run-time

In the following, we will discuss these different cases.

6. (BC) Before compilation

The conventional phase is before compilation. In that case, the code generator reads some configuration or maybe the source code and generates Java code usually into a specific directory separated from the manual source code.

In this case, the generated source code is not part of the code that gets into the version control system. Code maintenance has to deal with the code generation and it is hardly an option to omit the code generator from the process and go on maintaining the code manually.

The code generator does not have easy access to the Java code structure. If the generated code has to use, extend or supplement in any way the already existing manual code then it has to analyze the Java source. It can be done line by line or using some parser. In either way, this is a task that will be done again by the Java compiler later and also there is a slight chance that the Java compiler and the tool used to parse the code for the code generator may not be 100% compatible.

6.1. (DC) during compilation

Java makes it possible to create so-called Annotation Processors that are invoked by the compiler. These can generate code during the compilation phase and the compiler will compile the generated classes. That way the code generation is part of the compilation phase.

The code generators running in this phase cannot access the compiled code, but they can access the compiled structure through an API that the Java compiler provides for the annotation processors.

It is possible to generate new classes, but it is not possible to modify the existing source code.

6.2. (DT) during the test phase

First, it seems to be a bit off. Why would anyone want to execute code generation during the test phase? However, the FOSS I try to "sell" here does exactly that, and I will detail the possibility, the advantages and honestly the disadvantages of code generation in this phase.

6.3. (DCL) during class loading

It is also possible to modify the code during the class loading. The programs that do this are called Java Agents. They are not real code generators. They work on the byte code level and modify the already compiled code.

6.4. (DRT) during run-time

Some code generators work during run-time. Many of these applications generate java bytecode directly and load the code into the running application. It is also possible to generate Java source code, compile the code and load the resulting bytes into the JVM.

7. Generating Code in Test Phase

This is the phase when and where Java::Geci (Java GEnerate Code Inline) generates the code. To help you understand how one comes to the weird idea to execute code generation during unit test (when it is already too late: the code is already compiled) let me tell you another story. The story is made up, it never happened, but it does not dwarf the explaining power.

We had a code with several data classes each with several fields. We had to create the equals() and hashCode() methods for each of these classes. This, eventually, meant code redundancy. When the class changed, a field was added or deleted then the methods had to be changed as well. Deleting a field was not a problem: the compiler does not compile an equal() or hashCode() method that refers to a non-existent field. On the other hand, the compiler does not mind such a method that does NOT refer to a new existing field.

From time to time we forgot to update these methods and we tried to invent more and more complex and better ways to counteract the error-prone human coding. The weirdest idea was to create an MD5 value of the field names and have this inserted as a comment into the equals() and hashCode() methods. In case there was a change in the fields then a test could check that the value in the source code is different from the one calculated from the names of the fields and then signal an error: unit test fails. We never implemented it.

The even weirder idea, that turned out not that weird and finally led to Java::Geci is actually to create the expected equals() and hashCode() method test during the test from the fields available via reflection and compare it to the one that was already in the code. If they do not match then they have to be regenerated. However, the code at this point is already regenerated. The only issue is that it is in the memory of the JVM and not in the file that contains the source code. Why just signal an error and tell the programmer to regenerate the code? Why does not the test write back the change? After all, we, humans should tell the computer what to do and not the other way around!

And this was the epiphany that led to Java::Geci.

8. Java::Geci Architecture

Java::Geci generates code in the middle of the compilation, deployment, execution life cycle. Java::Geci is started when the unit tests are running during the build phase. As a matter of fact, you have to write one or more unit tests to configure and ignite the code generation.

This means that the manual and previously generated code is already compiled and is available for the code generator via reflection.

Executing code generation during the test phase has another advantage. Any code generation that runs later should generate only code, which is orthogonal to the manual code functionality. What does it mean? It has to be orthogonal in the sense that the generated code should not modify or interference in any way with the existing manually created code that could be discovered by the unit tests. The reason for this is that a code generation happening any later phase is already after the unit test execution and thus there is no possibility to test if the generated code effects in any undesired way the behavior of the code.

Generating code during the test has the possibility to test the code as a whole taking the manual as well as the generated code into consideration. The generated code itself should not be tested, per se, (that is the task of the test of the code generator project) but the behavior of the manual code that the programmers wrote may depend on the generated code and thus the execution of the tests may depend on the generated code.

To ensure that all the tests are OK with the generated code, the compilation and the tests should be executed again in case there was any new code generated. To ensure this the code generation is invoked from a test and the test fails in case new code was generated.

To get this correct the code generation in Java::Geci is usually invoked from a three-line unit test that has the structure:

Assertions.assertFalse(...generate(...),"code has changed, recompile!");The call to …generate(…) is a chain of method calls configuring the framework and the generators and when executed the framework decides if the generated code is different or not from the already existing code. It writes Java code back to the source code if the code changed but leaves the code intact in case the generated code has not changed.

The method generate() which is the final call in the chain to the code generation returns true if any code was changed and written back to the source code. This will fail the test, but if we run the test again with the already modified sources then the test should run fine.

This structure has some constraints on the generators:

-

Generators should generate exactly the same code if they are executed on the same source and classes. This is usually not a strong requirement, code generators do not tend to generate random source. Some code generators may want to insert timestamps as a comment in the code. Code formatting and comment changes are ignored by default. (Configurable.)

-

The generated code becomes part of the source and they are not compile-time artifacts. This is usually the case for all code generators that generate code into already existing class sources. Java::Geci can generate separate files but it was designed mainly for inline code generation (hence the name).

-

The generated code has to be saved to the repository and the manual source along with the generated code has to be in a state that does not need further code generation. This ensures that the CI server in the development can work with the original workflow: fetch - compile - test - commit artifacts to the repo. The code generation was already done on the developer machine and the code generator on the CI only ensures that it was really done (or else the test fails).

Note that the fact that the code is generated on a developer machine does not violate the rule that the build should be machine-independent. In case there is any machine dependency then the code generation would result in different code on the CI server and thus the build will break. It did happen with some early versions of some of the sample generators. It is an error of the generator itself.

9. Code Generation API

The code generator applications should be simple. The framework has to do all the tasks that are the same for most of the code generators, and should provide support or else what is the duty of the framework?

Java::Geci does many things for the code generators:

-

it handles the configuration of the file sets to find the source files

-

scans the source directories and finds the source code files

-

reads the files and if the files are Java sources then it helps to find the class that corresponds to the source code

-

supports reflection calling to help deterministic code generation

-

unified configuration handling

-

Java source code generation in different ways

-

modifies the source files only when changed and write back changes

-

provide fully functional sample code generators. One of those is a full-fledged Fluent API generator that alone could be a whole project.

-

supports Jamal templating and code generation.

10. Summary

Reading this article you got a picture why, how and when we generate code in professional Java development. I also briefly described Java::Geci, which is a framework to create domain specicific generators. You can actually start using it visiting the GitHub Home Page of Java::Geci.

Comments

Please leave your comments using Disqus, or just press one of the happy faces. If for any reason you do not want to leave a comment here, you can still create a Github ticket.